Over the last few decades, structural changes have affected the drivers of inflation, from domestic factors on which central banks normally focus, such as wages, productivity and inflation expectations, to more global factors.

Analyses performed using a new forecasting tool support these results. The latest information available indicates that inflation in Sweden will fall to 1-1.5 % over the coming years.

Which factors are important for inflation in Sweden?

Producing forecasts on inflation and pinpointing factors that are able to consistently predict inflation in Sweden is far from simple, it must be said. Multiple structural changes have affected the drivers of inflation over the last few decades. The fall of the Iron Curtain and the crisis in Sweden in the early 90s – with the collapse of the Swedish krona and a new monetary policy regime – were followed by the dot-com bubble in the year 2000 and the latest financial crisis a decade ago. Additional factors such as digitisation and globalisation have influenced wage and price formation during this period, and not just in Sweden.

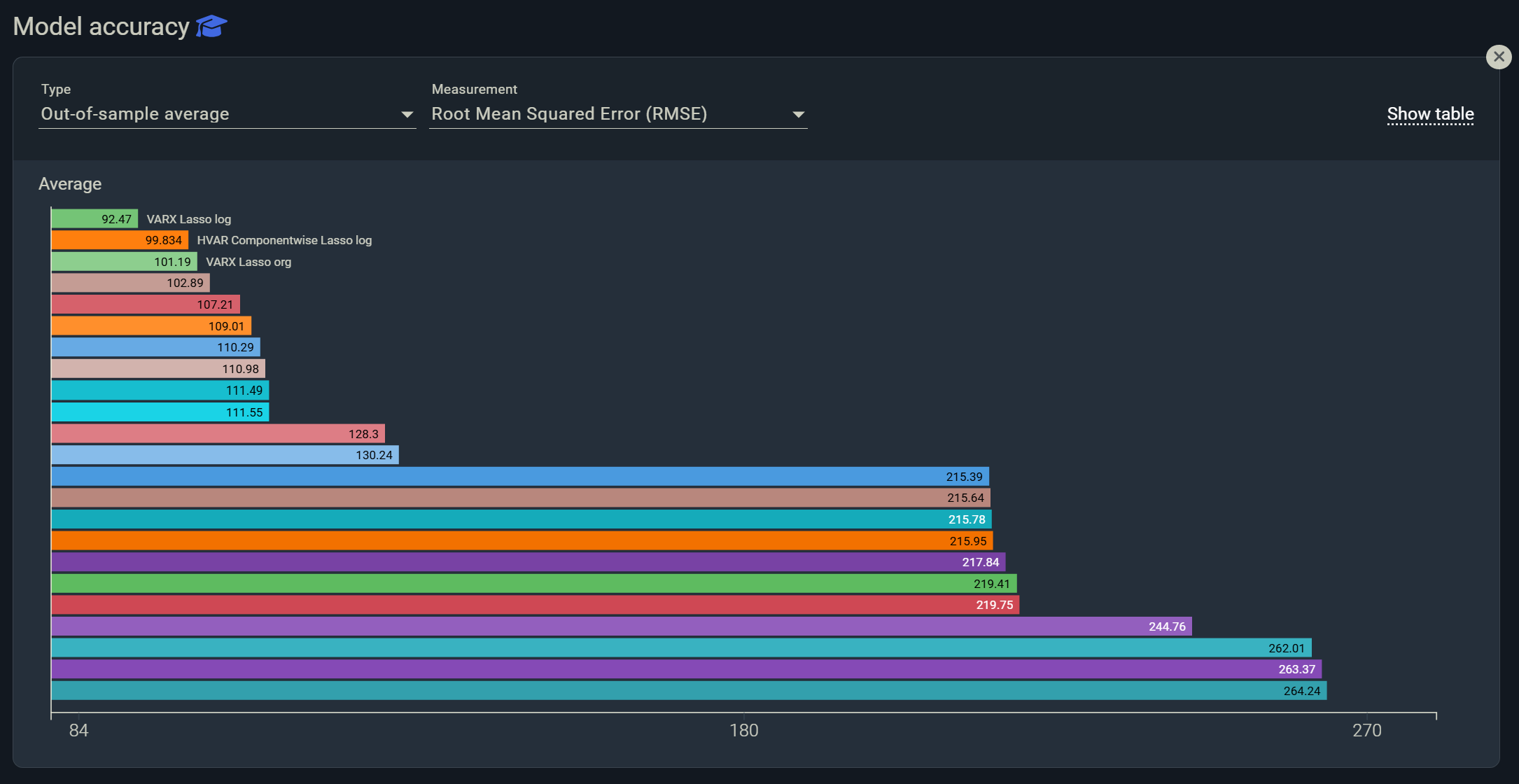

Using Indicio, we have tested some 40 different variables in order to forecast inflation 9 quarters ahead (for the technologically inclined, we used a model form known as VAR Lasso). We varied the time span for the calculations, and within these time spans we varied the amount of sample data on which to build the models and test the out-of-sample properties.

If we were to produce an inflation forecast for Sweden immediately after the financial crisis and were considering which variables to use, the most important ones that models would produce would be those you typically expect, such as wages, productivity and inflation expectations. Short-term bond yields, which were controlled more closely by the central bank (at least before the financial crisis), also revealed something about future inflation.

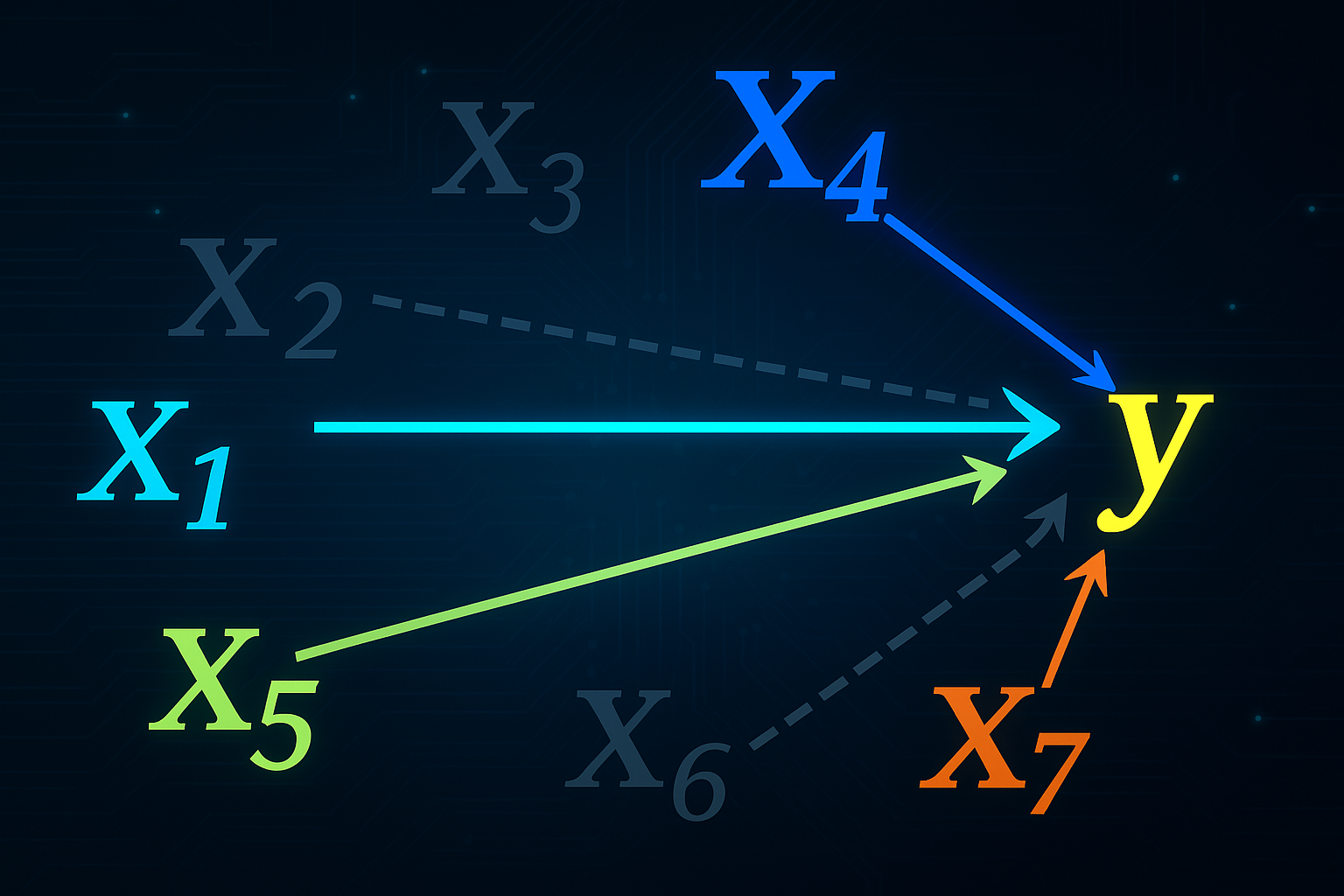

On the other hand, if we produce a forecast today with the same amount of data, going back 10-15 years, a different set of variables emerges as drivers of inflation. As previously, some of these are still linked to the level of activity in the economy and the labour market, but there are also new and more globally oriented variables that are not so easily influenced by monetary policy (see table below).

Today, the size of the labour force seems to be a more important factor than wage formation. One interesting observation is that the rate of increase in hourly wages and growth in the labour force previously developed more or less hand in hand, but after the financial crisis instead seem to vary in a countercyclical manner (see figure below). It is beyond the scope of this article to analyse the reasons for this, but we can note that something has occurred in this area that is clearly significant in terms of the inflation process.

Factors that reveal something about future inflation have varied over the years, thus making it more difficult to produce forecasts. However, it may be worth mentioning that some indicators do not appear to have any – or at least have limited – statistical significance in terms of the inflation forecast, regardless of the estimating period. Examples of this are Sveriges Riksbank’s own RU indicator of resource utilisation in the economy, unemployment and the Swedish krona’s exchange rate (measured by the KIX index). The size of the assets on the Riksbank’s balance sheet does play a role at the beginning of the period, but after the financial crisis this does not influence future inflation.

As we now have a fairly clear picture of which factors have best predicted inflation since the middle of the last decade, let’s see what they reveal about the coming two years.

Forecasts are unanimous – inflation will fall in the coming years

Indicio contains a library of some 30 different models that are evaluated by the system given selected variables. Indicio also transforms the variables into differential and logarithmic forms and different lag structures while testing the various forecasting models. The aim is to find models with a strong ability to forecast (“out-of-sample accuracy”) and that surpass a defined threshold value. There is no need to produce forecasts for the explanatory variables, since the system forecasts all variables included in the models and ensures that they are internally consistent. It is possible to test a specific scenario, or different scenarios, for variables you have a firm opinion about, but that lies outside the scope of this article.

We have experimented with a number of different variables distributed across some 20 sets and variations. Each set generates a number of different forecasts depending on how many model types are good enough to pass the threshold values. The outcome of these inflation forecasts may vary a great deal, perhaps up to 2-3 percentage points over a two-year term. Since it is impossible to know in advance which forecasts are best, each set of variables has been weighed together with their outcome in the “out-of-sample” tests. This should result in a solid, nuanced picture of the forecasting models’ outcomes (we have used MAPE – mean absolute percentage error – but using RMSE – root mean square error – or letting the models have equal weight would also work).

Provided that we do not face new structural changes that fundamentally affect the inflation process, such as limited global trade or reduced movement of labour and capital, the results are relatively unanimous. Inflation in Sweden will gradually fall over the next two years, having risen steadily from 0% over the past few years. Using the information we have today about economic and financial trends and the factors that provide information about future inflation, the best guess according to the models is that inflation will fall to between 1 and 1.5% in two years’ time (see figure below). There is thus no reason to be excessively concerned about galloping inflation.